We had one other set of flights that was about as easy as could be and they were called a TPQ flight after the radar that they used. After you took off and climbed out from Da Nang, you called the radar people and told them where you were. They would tell you to take a heading at a certain altitude between 20,000 and 30,000 feet. You told them how many bombs you had and once they identified you, they would turn you to another heading. You would continue that heading until you came to the drop point, and they told you that you had three, two, and one second to go to the drop point. Then they said ‘Mark’ and you dropped all your bombs by saying “Mark!”. It was an easy mission and most of them were in South Vietnam. It usually didn’t take more than 30 minutes and if you went out right away, you could finish the mission and be back on the ground within 45 minutes.

Sometimes I would return to the flight line about 3 or 4 o’clock in the morning and I would be asked if I wanted to turn around and fly another flight. It usually was an ordnance man, and I couldn’t say no to them. It was a lot of work loading 28 bombs on a plane and they were willing to do the work, so I couldn’t refuse to fly no matter how tired I was. Usually, they had just taken rocket or mortar fire on the base, and it was up to me to get those no-good so and so’s. After they got the plane ready, I would go out and fly a TPQ flight off the end of the runway.

We received incoming fire every other night while I was in Vietnam. The night before I was to leave to come home, something hit about 500 feet from the hut where I lived. Another night, there was an attack at 7 PM and I ran out of the club with a drink in my hand heading towards our bomb shelter. They usually tried to put their ordnance on the flight line or the runway. It’s odd because the damage to our morale would have been much worse if they hit our quarters.

Back to flying again.

I had another night in April 1968 that should not have happened as it did, I had someone other than Jack as a B/N. We were going on a TPQ flight, and it was raining as I taxied out. I noticed that I didn’t have any windshield air. It was the first time that happened to me, and I didn’t know whether it was serious or not. I asked the B/N if he wanted to go without the air. I said that I could see the center line of the runway, so I didn’t taxi back and take another plane. This was a mistake. I taxied out and lined up on the center line of the runway. It was raining harder as I began the take-off roll. As the plane picked up speed, I immediately lost the center line. I watched for the left side of the runway because I saw the centerline go off to my right. I couldn’t see anything except rain. All of a sudden, I saw the runway light under the left wing. All I could think of was that the bomb dump and the fuel pits were ahead of me. I pulled back on the stick and was surprised when the plane left the ground. I was flying. I went on instruments to fly the plane out of there and somehow, we completed our mission. When we came back it was no longer raining and we landed and taxied. I wrote on the yellow sheet that it had no windshield air, and it needed to be fixed.

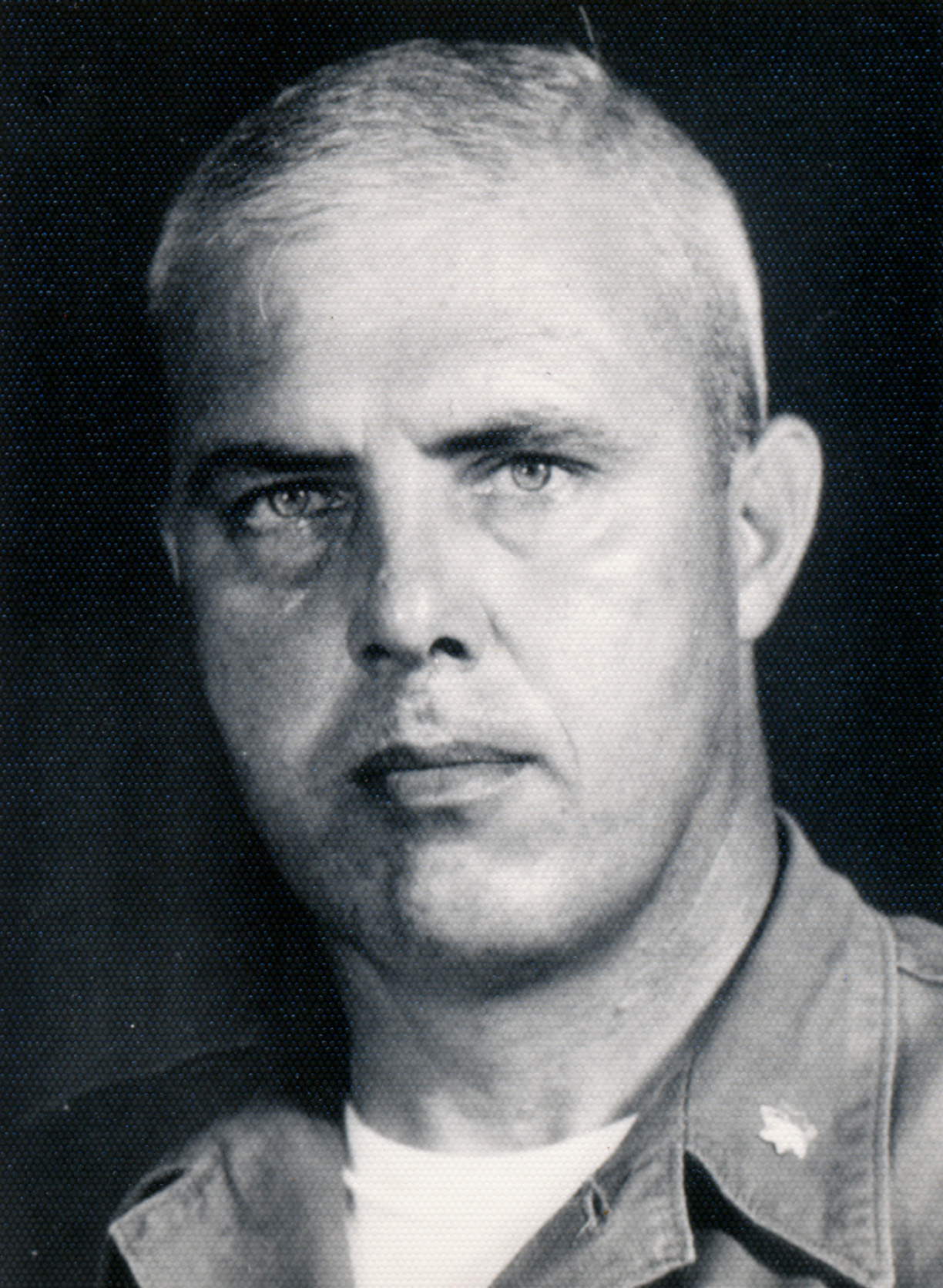

“My name is not on the Wall!”

Soon it was September, and I was waiting for my orders to the USA. I was very happy when I got on that commercial 707 and left Vietnam for the last time. All I could think about was that I was going home. I had made it through my year in Vietnam.

I left on September 5th, 1968. My name wasn’t on the wall! It possibly could have been, possibly should have been. But with luck and the grace of God,

“My name is not on the Wall!”