In 1934 there was erected in the center of the shtetl (the one-time market-place) the statue of a gentile man in rags leaning on a bear with one hand and with the second outstretched and pointing afar. This is a symbolic sculpture by “Zemeitis”, that is the main central part of Lithuania “zemaitiya” which shows that Lithuania has squeezed the Russian bear and on it is written: “I have been on the watch eternally and again won independence. ” It was a wonder that throughout all the years of Soviet occupation the statue remained unharmed and was not condemned. Since no Jew had erected it, one can live through it.

My shtetl is no fledgling. It was already mentioned in the annals of the 13th century. At that time, it was already an important center of Lithuania, specially in that part known as “Zemaitiya”; that is why Rasein suffered more than other villages in that country. When the Crusaders captured Lithuania, they destroyed Rasein completely.

When in the 16th century, Jews began to settle there, the village started to flourish. There sprung up streets with houses built up on both sides, shops that were communal enterprises and food industries with a bakery. But a peaceful existence was not sanctioned. The so-called fatherland war began when Napoleon assaulted the Russian Empire and Rasein again suffered both human victims and the destruction of houses and shops. Again, it fell to the lot of the Jews to rebuild Rasein, to construct new and many streets and alleyways. And that’s how it was when I still had no idea what Rasein meant to me. Nor did I know of Kedan whence my father had come or of the shtetl Krak from which my mother hailed. The first gift bestowed upon me by my parents was that I appeared in the world. It was indeed a present from God, but with the help of mother and father, since I did not yet understand where I was nor what was happening around me. And I had not yet acquired a name, but the smiles were forthcoming from all those who surrounded me.

I know not why I cried then, either because I wanted to be big like those around me or simply because I appeared in the world. Words were spoken, but I was unable to understand. In truth, the first gift was my surname which everyone knew. This surname has been with me from the beginning of my life and has remained with me to this day.

At the time, I did not think whether it was a name inherited from a long ago Sephardi tradition, or whether this was passed on from generation to generation because of their tailoring trade, which in Hebrew means a tailor (hayat). Probably this happened some hundreds of years ago, when surnames were first acquired. As I learnt later, it’s not such a simple thing for us Jews to go from Sephardi to Ashkenazi. Like for instance from Levy to Cohen; this is handed down from the fathers to their children.

At the age of eight days, I immediately received two gifts; a name and I become a Jew. From all sides there were shouts of “mazal-tov”, but I could not then understand Hebrew nor feel any pain. Upon my appearance on this earth, a theft took place. My mother told me later on that the midwife had taken the smock in which I was delivered at birth and apparently thrown it out. Yes, indeed, the first name that I received was David. Why the first? Because some time later I became seriously ill and upon the Bible, I was given another name in shul – Moshe. Since then I became known as Moshe David. And so too am I registered on my birth certificate. Even later, when I became a pupil in cheder and at school I was everywhere registered as Moshe David. But it being easier to call me by one name, I was called Davidke.

I never had toys bought in a shop apart from a ball. But children must play, that is the nature of the animal while he is still young and carefree; and why should I have been less than other children? So my father would invent home-made toys. Her would collect empty match-boxes, thread in cotton through the one side and tie it up and put another thread through the other side and join it up with a similar second empty matchbox creating a telephone through which I could “speak” with my sister or even my father from some distance. Or he would take two buttons, join them back to back making a knot in the middle with string. When the string is stretched the pair of buttons rise up and they twisted.

My father made me a “dancing doll”. He cut out the body separately from cardboard, the feet, hands, and head separately and tied them together from the back so that when you pulled the string the hands lift up and the doll turns its head and moves its feet. On Purim, my father made me a rattle out of wood to rattle during the reading of the Megilla. He even made me a top to spin on Hanukkah, also out of wood. Other and similar toys were created by my father. The only bought toy, as mentioned, was a ball, which my father could not of course make. But this often cost me a good belting. Firstly, I broke the glass of the buffet with the ball; then the ball drew me outside to the yard. And here too it did not behave respectfully. As if on purpose, it loved to hit the neighbors windows. The damage cost my father money and I got a belting with the strap. “Will this little boy become a decent human being or not?” my father would repeat with each stroke of the strap.

One even gets used to trials and tribulations. And so I got used to the strap too. Even though a day would pass in peace and quiet, I would already long for the strap and thought of ways and means of how to earn it.

My grandchild seats himself in a motor, presses a button and rides over the length of his parents’ flat. I had not such motors at his age nor any others that they have today, nor did I so much as imagine any such electronic toys. Or look at how small children sit in front of a computer and play all kinds of games. Could we even have imagined such games? In those days, we children couldn’t in our wildest fantasies have imagined such things.

We also didn’t live on the streets. There were apartments, though not with such large rooms as today’s, but we also lived, fantasized, dreamed, made-believe and grew up within a normal Jewish life. We studied in schools, colleges, cheders and yeshivas, and nonetheless we developed no worse than the present-day youngsters.

So, what other “gifts” did I get?

Just like that, simply – Davidke, the Rasseiner. This had, on other occasions, caused me grief. While I was studying at the Telzhe Yeshiva, I would be invited for Shabbat Kiddush to one or other home. Once, someone came to the yeshiva to invite me and asked where I was from. When he heard that I was from Rassein, he went pale poor man and asked my pardon saying; “I’ll invite you another time.” To this day I’ still waiting for this invitation. Why did he back off?

In those days, every Lithuanian shtetl had a nickname; the Widukler goats, the Kelmer sleeper, the Keidaner hunchbacks or cucumbers. Rassein too had a nickname – the Rassein glutton. Perhaps when the Jew heard the name Rassein, he took fright that I would gobble up his whole Shabbat table and leave his family hungry, so he regretted having approached me. But I had never been a glutton, just like every other Rassein Jew. I was begun to be called a Rasseiner when I was in Ponevez, where I studied at the Rabbi Kahanemen School after which I went to study in Telze. Was I called a Rasseiner because it was more convenient to do so or as a warning to others that they were dealing with a glutton?

What else is there to tell? Among us Jews nothing is done just so, without any specific intent. In that case, the present I received of the name “Rasseiner”, so be it, one can live with that. What did I care. After all, others were called: the Berdichever, the Odesser, the Vilner, the Polisher, the Lithuanian. It was worse that , instead of being a glutton, I often went hungry. It was the custom to invite young boys for Shabbat or just for the kiddush. So it indeed happened that I was sometimes not invited, when they learnt that I was from Rassein. I can only tell you loud and clear that this was sheer slander. The Rasseiners were never gluttons. I am sure too that most of the Jews from Keidan were not hunchbacks and that not all Widukler Jews kept goats and that the Kelmer Jews were as regular as all normal Jews from all the other villages of Lithuania. The poverty in Rassein was no greater than in other villages and the eating habits there were normal as elsewhere. Believe me, I would eat in moderation and sometimes even go hungry, but I blame no one for that. I alone was to blame, for I could certainly have had such a nickname. But why was “glutton” so widespread?

The tale goes that years ago a Rasseiner young man married a girl from a wealthy family. Naturally, the in-laws ordered a lavish feast and invited the aristocracy of the town where the bride lived.

After the ceremony under the chuppa, when the company sat down at the tables as was the custom, the bridegroom sat down next to the bride at the top table. He was starving from abstaining from taking food all day, apart from which he had never tasted such delicious delicacies before. So, he set upon the food with gusto or more accurately, he overate, and suddenly, feeling ill, he became white as chalk and couldn’t leave the table in time. In the presence of the important guests, the bride and his new in-laws, he vomited all over his new suit, the tablecloth and around him, over the bride’s silver dress. A turmoil broke out; the match was off and the bride divorced him on the spot. Had this all been left between the sides, the matter would have been forgotten. But no, what do our Jewish women in general and in particular do and to make things worse, also the close relatives of the bride herself, they make a scandal throughout the world that the Rasseiner Jews are gluttons and that one should not marry their boys or their girls. In time, this decree was forgotten, but the nickname “glutton” stuck.

When I became a bit smarter, I would reply: “I come from a shtetl not far from Kovno.”

After finishing the cheder, my father sent me to the Ponevez school named after the famous Rabbi Kahanemen. But how can one send away a young child all on his own to a strange town?

“My son, you are going away to study in Ponevez. You will be helped with everything by a relative from Shidlever, called Shifrin.”

“He is also studying in that school?”

“No, he’s much older. He’s studying in a yeshiva.”

“That’s fine, dad, Shifrin is Shifrin, to me it’s all the same. Do what you think is best.”

Thus began my wanderings. Ponevez made an impression on me of a large town. “It is not so large as it is well-known in the world”, Shifrin explained to me. It is famous for its big yeshiva. The town is in fact larger than Rassein and is divided into two parts – the old city and the new. The first part is already mentioned 500 years ago. The town is split into by the Nevezis River. In the beginning, the town was built on the left side of the river; the right side was overgrown by a thick forest which prevented the town from expanding its borders on that side. Almost all the town’s twenty-eight streets and alleys were on the left side of the river, and there lived a goodly portion of Jews. A steel bridge over the river unites both sides of the town and the town itself with the rest of the country.

The Jews here were not idle either – they were involved in commerce, factories, trades; they were teachers, doctors, there was a schochet (ritual slaughterer), a few mohalim (circumcisers), some rabbis – Hassidic and Mitnagdic (opposers of Hassidism) synagogues and an old-aged home, a girls’ high school and a general school, a pharmacy and a bathhouse as well as the well-known yeshiva, all established by the Jewish community.

“This is all very interesting to know, but where will I stay?” I interrupted Shfrin’s story.

“I have a good suggestion”, one of his acquaintances interjected. “At the home of the old shochet, 8 Sadever St., there is an empty little room which he will no doubt be prepared to let cheaply.”

And indeed that is where I settled in.

Some time later, I learnt that most of the Jewish communal institutions support the city Rabbi Kahaneman, even a Jewish hospital and bank, not to mention the yeshiva, all of which were in his name and supported by him. To this end, he would often go to America for financing.

Here, in Sadever Street, (SODU), I lived for two years until I finished my schooling and moved over at my father’s wish to studying in the Telze Yeshiva.

Since then, many decades have flown by. I lived through imprisonment and exile, frost and heat, felt the “beauty” of Soviet power organs, but my dream lived inside me and gnawed at me to break out from the “paradise” and then the blessed hour arrived. I received permission to go to Israel. I travel to Riga, to the ancestral grave, the cemetery where my late father is buried under the beautiful name of “Shmerele”. I then go to Vilna, where my sister’s son, Mulla Yalowtzki, has a car and takes me all over Lithuania, over the towns and Shtetlech that once existed and were connected to my life and bid them farewell. I went to Poneez, to 8 Sudo Street. Not a Yiddish word to be heard, nor a Jewish face to be seen. The light is there, the candles have burnt out. Gone are the old-time proprietors. All is bleak and desolate, the town is judenrein, but much dirtier than before. The Lithuanians did not get rich, even from the goods and chattels they looted from the Jews. So, why indeed is the street called Sodever, or in Lithuanian “Sodu”, i.e. an orchard. The street was populated by Jews. Each family had its own house with a courtyard and orchard. In spring the whole street would blossom with a variety of coloured flowers.

Yes, I remember it well; it’s the same house. Now it’s peeled of its green colour and on the walls hang scales like those of a fish mixed with shells. The windows face the street, the entrance is through an opening in the gate. You start off by going into the courtyard next to an orchard. Here is the porch. You knock on the door, kiss the mezuza, and the old shochet or his beautiful young daughter opens the door with an amiable smile showing the dimples in her cheeks, as if she had squeezed them there. Here, the “window” on the left is that of my room. Next to my room was that of the owner’s daughter. The window of her room was next to mine and a second window was on the side of the orchard. Also, the entrance to her room was a separate one. I don’t remember now whether there were any other children, but I had not forgotten the daughter. She was often smiling. The young men would say that she was a beautiful as an angel. In truth, I had never seen an angel. Her father, my landlord, was a shochet, from a family of shochets, and though he was quite elderly, he was still a good slaughterer.

My guardian in Shidlever would often come to visit this girl. This yeshiva scholar would study during the day in the yeshiva and the evenings he would spend with the girl. What he would be doing until late at night, I could not imagine, but one could often hear through the adjoining wall the girl’s laughter. At first, I was indifferent to this, and I would fall asleep and her laughter would not disturb me. The young man was intended to keep an eye on me. Possibly that was why he would stop over with the family. The two rooms he had divided by a thin wall with a door. The wall and the interleading door were closed up with wallpaper. A thin crack remained under the door. In due course, however, my curiosity was awakened. Somehow, the laughter did not seem quite natural.

I didn’t have the audacity to ask Yosef what he was doing there. The shochet’s daughter had a number of Jewish girlfriends, who would meet her in the orchard. I, as a young boy, had no connection to them and their company did not interest me.

SODEVER STREET

Sodever Street is not a long one, but it was rich in trees and bushes on the pavements on both sides of the street. The branches of the raspberry bush pushed and squeezed themselves through the fence as if they were begging me to have pity on them and pick their berries as it would be a shame to let them fall on the ground. I would throw the berries into my mouth, as taking them with me might be considered theft. Higher up above the fences hung larger and thicker branches with apples, pears, plums and cherries. Plucking them off forcefully was not my style, but picking their fruits up from the ground, thanking them with me, washing them and then eating them was my idea of a lavish breakfast. I would often share it with my friends. My parents would wonder how it was that I was able to save money from the little that they sent me.

Now the branches no longer hang over the fence; the trees and bushes in the street have become more sparse, but the name “Sodever” has remained. Also, the gate is still there with its odd opening on 8 Sodever Street, but the gateposts are sunken into the ground as if they wished to follow their owners.

“Should I enter into the house or not?” I wondered. I was overtaken by curiosity. In truth, what would I ask the new tenants? Did they kill the owners? And even if they did so, would they admit to the truth? All of a sudden there was a kind of roar. It was the barking of a dog from the yard. Obviously, this was not a small dog, though I could not see him, I heard his barking quite close. Does he want to greet me with a “welcome” or berate me for showing up there, telling me that I have nothing to do there. I stood still and thought for a moment. But while thinking, of their own accord my feet started retreating as it were when one walks backwards from the Holy Ark in the synagogue. My eyes became moist as I twisted in another direction at an ever-increasing pace towards the place where I had studied.

En route I saw another familiar house. This was where a well-known Jewish doctor had lived. He took out my tonsils. I am lying on his sofa after the operation. On a stool nearby is a basin, deformed like an ear and full of blood; my mouth feels as if there is a constant scratching there and I’m spitting blood.

“Lie down here for a few hours. Tell me when you’re feeling a bit better,” he said.

I hardly managed to spit out a few words. “Doctor, I’m finished.” “What do you mean finished? Open your mouth,” he ordered me “Lie down for another short while and then you can go home.” And he proceeded to tell me what I should eat and what not.

Like a drunk, clinging to the walls of the houses and the fences, I barely managed to reach my abode. My parents learnt of the operation only after I had recovered.

Should I go into the doctor’s house and greet him?

I see a gentile woman standing near the house. “Who are you waiting for?”, she asks.

“I remember the doctor, is he here?”

“Your doctor together with all the other doctors and all the Jews in the town have long since gone to the other world.”

I couldn’t say anything more to her.

I walk on and on. Here is the street where my school used to be. All the surrounding houses have remained intact, the school is no longer there, sunk into the earth and swallowed up In its place, there is a new building, a typical modern residential house, without architecture, no beauty. Perhaps I am mistaken. I enter the courtyard. Here we had spent our school breaks, jumping around, volleyball, or testing our balance by walking on a wooden beam. At the side were a table with benches, where my friends and I would sit and discuss the daily news. Is this indeed the same courtyard? Here too a tube has been dug into the earth for the purpose of airing carpets. The closet which had stood in the corner of the courtyard has disappeared. In its stead there is a sort of stable containing some booths.

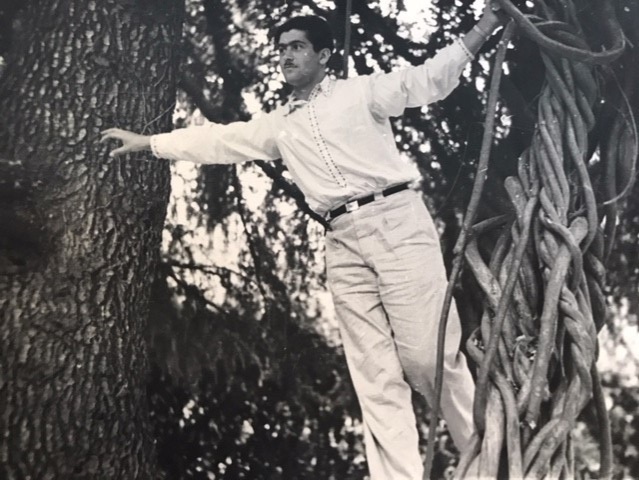

“Still, the earth is round,” I thought. “So perhaps all the old properties had rolled down, but why in particular the Jewish ones? And the trees planted by the Jews are still standing as before. The pupils who used to clamber on these trees fell at the hands of the murderous Lithuanians. I remained still for a few short minutes while my clothes became wet from my falling tears, and I quickly left the place.

The car took me further to Telze.

My father had been a simple, religious Jew. He would often go during the week to pray “Shachrit” (early morning prayer) at the first minyan (quorum of ten). He would awaken me too and take me with him to the shul (synagogue). He liked to hear a sermon from a preacher or a city rabbi, and learn a page of Gemorrah (Talmud). In our home, kashrut was strictly observed as well as other Jewish ritual laws. No doubt he had dreamed of having a son who was a “yeshiva bocher” (cholar at a yeshiva). So he sent me to study at the Telze Yeshiva, where I also got room and board. I even got used to sleeping on a worn-out wooden bench. Apparently, not one-tenth of the pupils spent overnight on that bench as I did. We were not poor, God forbid, but my late father was no spendthrift. But on one thing he refused to economize – and that was charity. At home on the Sabbath, we would frequently have a guest for kiddush and a meal.