In 1997, I got a call from an engineering firm headquartered in Houston, which was planning to do consulting on two refineries in Nigeria. The Nigerian government wanted to get out of the oil producing business because they were unable to keep the refineries operating at 100% and were losing money. Mobil Oil Company was gathering data to inform their decision on whether or not to buy the refinery, and our reports would be part of that process.

I flew out of St. Louis ending up in Amsterdam, where I ran into one of the individuals I worked with on another project in Houston. We both had reservations at the same hotel in The Hague where we stayed for a week. The team consisted of four of us in refinery operations and four mechanical engineers. After the week, we all loaded up on KLM, the only major airline that would fly into Nigeria. Lagos is the capital of Nigeria, the most populous city on the African continent, and one of the largest metropolitan areas in the world. We were housed in a Sheraton hotel in Lagos, though we would later be separated and assigned to two different refineries. Across the alley from the hotel, there was a nice, big building partially finished, but weeds were growing up around it. I asked one of the people that worked in the hotel why construction had stopped on it. I was told that every time a new administration took over the government, any projects started by their predecessor were shut down and not finished. It was to have been a parking garage. This was my introduction to the graft and misappropriation that was rampant in Nigeria during nearly three decades of unrest, in which there were several successive military coups and the country was governed by dishonest military leaders, one of whom, at the time of his death in 1998, had several hundred million dollars stashed in European banks.

While in the hotel in Lagos, we determined who would go to which refinery. The individual who was to work with me in conducting an operations study was from Venezuela. He had been the assistant superintendent of a Venezuelan refinery but when things started to go badly there, he moved to Houston and started doing consulting work.

Flying out of Lagos—not an international airport—was rather an adventure. Each passenger was weighed with their luggage and belongings so that the exact weight of the plane was known. The runway was not long enough for takeoff of these large airplanes, so when the plane was ready, soldiers, some of whom had been standing by in the concourse, would open a gate in the airport’s chain link fence, and stop traffic on the four-lane highway that ran perpendicular to the runway. Then the plane had access to an additional 60 feet of extended runway across the highway.

My partner and I were assigned to check over the refinery in Warri, Nigeria, but when we arrived, the airport there gave us a forewarning of what we might find at the refinery. The people movers weren’t working. It was raining and the ceilings were leaking. When we went to get our luggage, parts of the belt were missing and we could see suitcases had fallen through the empty spaces. I told my partner that maybe we didn’t even need to visit the refinery if the airport was any indication of how things worked here. We stayed in a poor-quality hotel one night, certainly not like the Sheraton we had stayed at in Logos. The next day we were taken to a compound of probably five or six houses surrounded by an eight-foot concrete fence, the top of which was embedded with broken glass to keep out intruders. The compound was owned by the engineering company that we represented; their four full-time employees lived and operated out of this compound. My partner and I were housed in a two-bedroom house with a kitchen and living room. The first thing we did when we were assigned a driver and car was to shop for groceries. There was not much selection at the store, so we ended up with mostly eggs and a few other items. We cooked eggs or ate at the local restaurants for our evening meals. For lunch, we frequented the refinery’s cafeteria, where we were the only non-Nigerians. The managers’ cafeteria was off limits to us. The cook realized that we didn’t like hot, spicy food, so we were directed to what was less spicy.

In the mornings we went to the refinery on a road with potholes big enough to hide a Volkswagen Bug. Seriously, the potholes were about a foot deep and we had to dodge on-coming traffic to go around them. When we arrived at the refinery, we met two individuals in engineering who would take us where we needed to go and make sure we had everything we needed. My partner and I observed the different areas and the operating units, getting information by talking to the operators and their supervisors. Their bathrooms were just partly operational; behind the wall, about half of the copper tubing for the waterline was missing.

I was to become convinced that Nigeria was the most corrupt place I ever visited. It seemed that everybody was stealing whatever they could get their hands on, and punishment was non-existent.

We spent the next two weeks reviewing the refinery, which had been owned by oil companies outside the country before the Nigerian government took it over. It was our conclusion that the manager for each of the units was stealing the operating money instead of putting it back into running the refinery. For example, when chemicals were needed for operations, the money to purchase the chemicals ended up mostly in the pockets of the managers. Funds for repairs went the same way.

When the crude oil came in, it was split using heat and pressure, creating a top product lighter than the bottom, which is more like a tea kettle, top is steam and bottom would be where you would find lime build up. The refining process continues to split the resulting output into lighter and heavier materials until eventually products such as gasoline and propane are created. If any of the units was down and couldn’t take the product being sent to it, there was no other place for it to go and no option but to send it to the flare. To stop one unit was to stop the entire refinery. The refinery’s flares burned fully open all the time.

The other team was at another refinery, finding the same problem: operation of the refineries wasn’t the problem, corruption was. In Americans refineries, safety is of primary concern. Some workers at the Nigerian refineries wore flip flops or were barefoot, confirming their third-world situation. The Nigerian government owned most businesses outright, or at least had a hand in them.

The Nigerian army and police were corrupt also. As we drove to and from the refinery, we’d see policemen stopping people on motorbikes, the main transportation there. The officers would be talking to the people, trying to find out where their pocket money was, and would just help themselves to it.

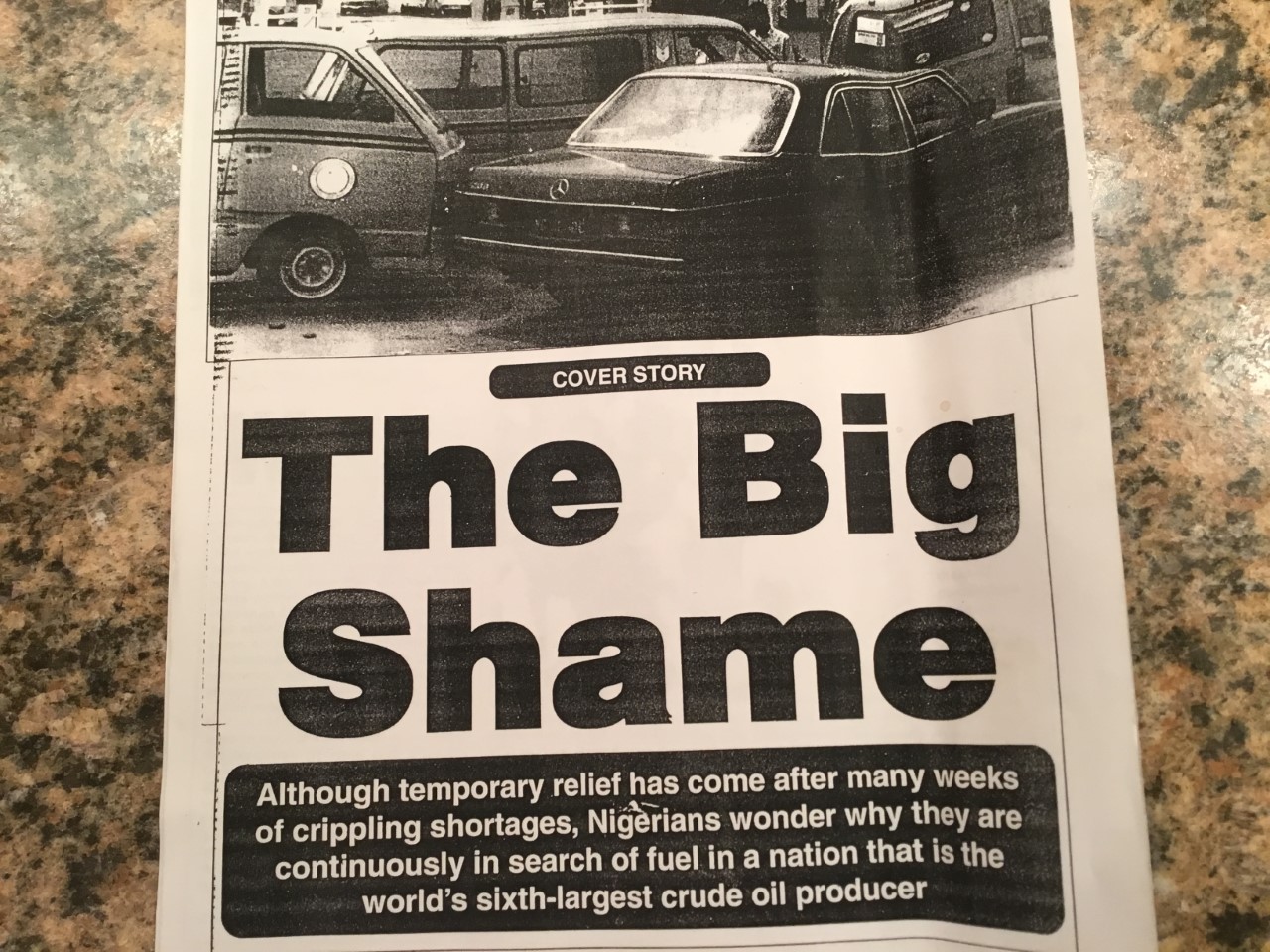

An English newspaper had an article on the front page with pictures of people holding cans and bottles—anything that would hold liquid. As the article explained, it happened quite frequently that somebody would drill a hole in a gasoline pipeline, and it didn’t have to be a very big hole because of the pressure on the line. The leaking gasoline would create a pond maybe as big as a house and the people would wade in with their containers. The gas stations always had lines because gasoline was scarce. Motorbike riders bought their fuel by the liter, sometimes from people standing at the curb in front of their house, probably peddling gas gotten from one of the holes. Sometimes someone would generate a spark with metal cans or some other way, causing the entire pond of gas to flare up into a huge fire. Those who got burned would not go to the hospital for fear of being arrested for stealing. They would use some home remedies and heal, or just die.

The whole country, from the locals all the way up through management, was corrupt. It was eye opening, and I did not enjoy being there.

At the hotel, I had bought a pair of bookends carved of African ebony blackwood. One side was a woman; the other, a man. I had packed them in my luggage. Nigeria didn’t want foreigners removing any items from the country that were considered part of their ancestry, and inspectors at the airport checked for such things. Before the inspector opened my bag, I reported my purchase, and had to pay him the equivalent of ten dollars or so to let me go through, another indication of the endemic corruption there. If a person wanted to put a bomb on an airplane, I suppose there was a way to pay off the inspector. As we entered the concourse from where our plane would depart, we were approached by one of the army officers who asked if we “had anything” for him. There was no other reason for him to stop us. I told him we had just paid the last of the Naira we had to a shopkeeper, who had tried to get additional payment from us by asking if we had any watches. I had replied to him that I had only the watch I was wearing. Next time, he told us, we’d better bring him a Mobil watch. It seemed everyone had his hand out, or a hand in your pocket. I don’t know how the locals could even survive in a place like that. I guess eventually they all learn to live that way if it goes on long enough.

We had made notes of what we saw and gathered technical information on production volume and the like, that we took back to the Netherlands to write the reports of our findings. In some cases, what we wrote was verifiable; in others, we could only describe what we had seen.

When we were safely back in the Netherlands, Pat came over to spend the three or four weeks we needed for writing the reports. She flew into Amsterdam and I caught the train to meet her there. The Amsterdam airport and railway station are in the same location. No one was allowed to wait in the arrival area, so I walked around keeping an eye out where I thought she would come. And finally, she did. Our team was staying at a hotel in The Hague, so we took a taxi there.

Pat was able to meet up with our English friends, the Edges, who had brought their camping trailer to the mainland. While I was going to the office to write reports, she and the Edges took in the sights. Among other points of interest, they visited Delft, famous for its blue pottery. In the evenings, we would go out to a nice restaurant with them. When I was off on the weekend, we went on an art museum excursion, seeing works of famous Dutch artists. After the Edges returned to England, Pat and I enjoyed walking along the canals; it seemed any place was as accessible by boat through a canal as by a street. We saw boats approach a small bridge, where the boater would tie up, hand-crank the bridge open, maneuver the boat through the opening, then hand-crank the bridge closed again. Bigger roads and highways had bridges high enough for boats to pass under. The homes we saw on our walks, though often small and nearly identical to the other houses in the neighborhood, commonly had beautiful flowers out in front, and the friendly people tending them enjoyed visiting with us.

On the 20-minute walk from our hotel to the office, I often saw a lot of people riding bicycles. Outside the train stations, it was not uncommon to see perhaps 500 bicycles parked all in one area, provided by the government for free public use. People would ride to wherever they were going, then leave the bike for someone else to use.

The guys in the office invited my partner and me to have a beer after work at an establishment that was featuring live music that evening. Two ladies, probably in their fifties or sixties, were also enjoying the music as they each rolled a baby carriage, back and forth, back and forth, and tended to the child. Later, as they pushed the carriages past us, we saw that the babies were lifelike dolls. We never did figure out what that was all about.

We were very conscious of the effect World War II had on The Netherlands, and how it had stayed with them for a long time. Amsterdam is a beautiful city with numerous museums; the history has been carefully preserved, even of such places as where American servicemen were housed. We visited the Anne Frank museum and took a guided boat tour through the canals.

When we rode the rails between Amsterdam and The Hague, we saw many little houses about the size of a single room. People from the city would have gardens in the country and these were their weekend shelters with a bed and cooking facilities. Amsterdam had many street vendors and performers. There were also areas where the wind was blocked and people sunbathed, topless women even. I suffered only two black eyes as a result of observing this phenomenon.