I graduated in 2003 as an armor officer and I had orders to go to Fort Carson, Colorado. I was just barely highly ranked enough at West Point where I got the absolute last slot to go there. But then as I was graduating from Fort Knox, someone came to our officer class and said, ‘we need officers to volunteer and take national guard platoons on deployment.’ They needed 14 to step up and do that and I was one of the ones who volunteered. I was also really proud that 13 of the 14 volunteers to go to war were my classmates from West Point.

I met the unit shortly after Christmas in Fort Bragg and we were at Fort Polk by January for a month training rotation, and then we were off on our deployment to Iraq by February of 2004. I wasn’t quite sure what to expect going to lead a National Guard platoon from West Virginia. My platoon was mostly white with the exception of one soldier. I stuck out like a sore thumb in most ways – I’m this black Californian who went to West Point who now leads soldiers from the West Virginia National Guard.

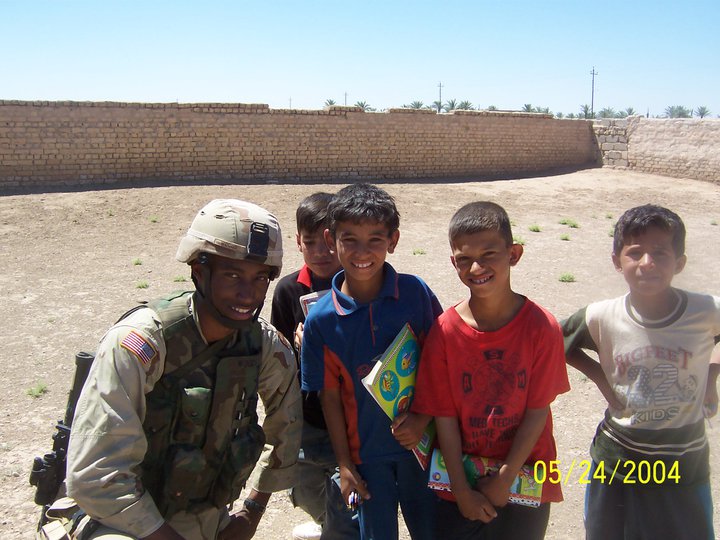

But we shed all of our differences, politically, ethnically, geographically. We quickly grew to care for one another and got to know one another very, very well and we were pretty quickly off on a pretty important and somewhat scary journey together. Once we deployed, our mission in Iraq really varied. A lot of training of the Iraqi Army and a lot of convoy escorts. So we spent a lot of time on the road doing a lot of route clearance.. We had a sector with a very large perimeter – we’re talking probably hundreds of square miles per platoon of 16 that we were supposed to be aware of. That deployment was north and east of Baghdad between the Iraq and Iran border. We had a lot more smuggling so you know we set up a lot of checkpoints, did a lot of searching of vehicles and searching of places that we thought were ultimately weigh stations for insurgents who were on their way to support the more kinetic activities that were going on in Baghdad and the larger cities.

We were always sort of on the go but you find ways to just kind of enjoy life – create some normalcy and hang out with one another. Run a lot, work out a lot. I’d probably scream today but you spend a lot of time with this low-cost, low-bandwidth internet cafes. They were pretty strict on not allowing WiFi where the housing area was so I remember sort of making this daily multi-mile walk in 120 degree heat to this very shabby internet cafe. I remember ploughing through multiple seasons of the West Wing on my now very dusty computer. You kind of break up the key elements of daily life, you know?

Later in our deployment, we were doing our sort of standard early morning route probably just after 6 or 7 in the morning and I remember for whatever reason that day we decided to mix up the convoy order so I was the second vehicle. We were cruising at 45-55 mph down this highway and I remember just looking out the window, scanning the road or whatever, and then all of a sudden, I remember I opened my eyes and the next thing I know I’m looking at what appeared to be just a wall of dirt and smoke and debris and it didn’t make any sense. I almost feel like everything kind of slowed down. It’s also kind of a weird sensory experience. I remember just looking at this wall of dirt and debris and having to kind of wrap my head around, what in the world am I looking at? This is extremely strange and then I realized, well wait a minute, that’s an explosion and there was a vehicle in front of me and I can’t see the vehicle. And then you know I sort of didn’t realize it but everything was kind of silent, and the next sound I heard was me talking on the radio. I was checking on the status of the vehicle ahead of me. It was a complex attack and so the insurgents set off an IED but then they also started firing at the convoy. I remember giving orders to the platoon to fire back but to also push through. The vehicle in front of us, the guys were banged up, a couple of them got concussions, certainly busted eardrums, but none of them permanently damaged. That was the closest I came to losing soldiers was that particular attack. A couple of guys got purple hearts for that and it really shook them up.

It’s interesting looking back on my time in Iraq. I felt like we as a nation kind of rushed to judgement. It didn’t appear that there was much of a connection between 9/11 and Iraq and Saddam Hussein, it felt like the evidence was confirmation biased, everything felt just felt off to me, you know? But I knew that I didn’t want my soldiers to pay the price for what felt like a bad political decision. I think the mission becomes your fellow soldier, right? The mission becomes, I will execute orders and I will carry out missions that are not illegal, unethical, or immoral and first and foremost I’ll be thinking about the safety and wellbeing of my fellow soldiers. I also recognize that soldiers at war can make mistakes and those mistakes can do real damage to innocent civilians and property, so there’s a need to make sure you conduct yourself ethically and you need good officers to do that.

So it became very easy to be really motivated to lead my soldiers well, take care of their wellbeing, bring them home alive, and make sure that we didn’t do anything that we would be ashamed to talk about with our families when we did get home. Over two deployments, that was something that I was really most proud of was the ability to do that and over both deployments, 81 soldiers all of them came home alive.

We got home just shortly after Christmas and I remember constantly scanning the room and constantly looking for violence or danger to unfold without warning. You don’t realize it but your body is sort of like a naturally permanently clenched fist and it takes a long time for that to unwind and unravel and for you to relax. You observe your civilian peers and friends and everyone else, and for them the war was nothing more than something that scrolled by on the bottom of the screen. This thing that felt all-consuming and very important to you and your fellow soldiers was completely unimportant to people back home.

Part of that is a national decision not to fully involve all aspects of society in carrying out American foreign policy. And so it becomes this thing that a very small number of people will do and no one outside the military has to make any real sacrifices. I wouldn’t say that I was mad or cynical but I had this reflection of, ‘huh, I guess what I did doesn’t really matter to other people.’ I remember feeling so out of place as a result of that.

My next assignment was to basically pick up where I left off so I was going to go to Fort Carson, CO and my unit that I was supposed to go to had just left for Iraq. I remember thinking, well, I feel so out of place, I don’t want to stick around. I don’t want to be in the United States.

So I requested a waiver to turn around and join the 3rd ACR in Iraq. I had five months between deployments, and I thought I was well enough rested, I thought I was prepared to go back but the moment I got back overseas and caught up with the unit, what took four or five months to get really exhausted during the first deployment, it probably took one or two months to feel just as sort of burnt out and tired.

When I arrived, the regimental commander of the 3rd ACR was Colonel H. R. McMaster, the hero from 73 Easting who I read about in school. We were this really well-equipped, really highly skilled unit and we were in a much, much more dangerous place in Tal Afar, which was the north west of Mosul. Tal Afar had become this real stronghold for Al-Qaeda and Iraq and other insurgent groups. When I got there, I quickly took over the support platoon, which is the platoon that’s responsible for food, fuel, ammo, logistics, all that sort of stuff.

So I think 64 soldiers were in the platoon and a lot of fuel trucks, which is a scary thing to drive around; I have a lot of respect for guys who can do that day in and day out. There were whole swaths of the city that couldn’t – you know American units could not patrol without immediately coming under fire and so it became very clear that this was a city that could soon be out of control if things didn’t change. So that deployment was where H.R. McMaster and my squadron commander, Lieutenant Colonel Hickey, developed this precursor to what was the clear hold and build strategy. This was 2005, and we built a huge dirt berm around the city. We set up checkpoints and started to clear out the city using psychological operations and pamphlets and leaflets and all that stuff. We made it clear that if you’re still here after x date, you’re saying you’re here to fight. This was I believe at the time a 250-300K city; it was gigantic. We cleared out this whole city and then I think we had an additional unit from the 82nd Airborne join us to sort of plus us up, we had additional squadrons sort of flex resources towards us.

I think we probably went 30-45 days of sustained operations. I remember fighting alongside kurdish peshmerga. They were incredibly skilled fighters which sort of makes our most recent decision to betray them as an ally really kind of sting. I remember, I think we had about 2,000 Kurdish troops who were fighting alongside us. It was really incredible to see how skilled and capable they were.

The operation was successful and we essentially moved off of our FOB and into the city. We built over a dozen really well hardened checkpoints, compounds within the city, causing my role as a support platoon leader to become much more dynamic. And the strategy worked. We cleared out the bad guys, we moved into the city, and we held it and what that immediately did was made it clear to the Iraqi population that you can actually trust us: If you have information about bad actors you can tell us because we’re not going to go away at night to go back to our FOB, you can trust us to use this information to stop these people. And things really changed significantly from that point forward and I think that’s why it became a model that people like General Petraeus later integrated into his kind of broader approach for all of Iraq.